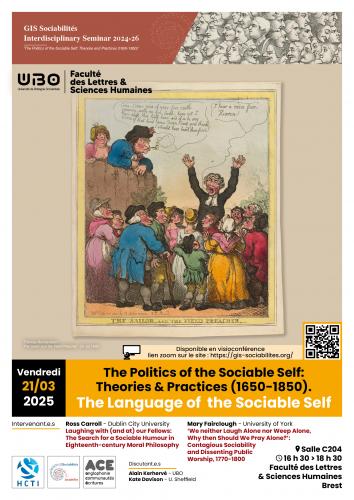

GIS Interdisciplinary Seminar: 'The Language of the Sociable Self'

GIS Sociabilités seminar 'The Politics of the ‘Sociable Self: Theories and Practices (1650-1850)'

Third thematic session on 'The Language of the Sociable Self', 21 March 2025 (16:30 - 18:30) at the Université de Bretagne Occidentale, Faculté Ségalen (room C204)

Session chaired by Alain Kerhervé (UBO) & Kate Davison (University of Sheffield)

- Dr. Ross Carroll (Dublin City University) - Laughing with (and at) our Fellows: The Search for a Sociable Humour in Eighteenth-century Moral Philosophy

- Dr Mary Fairclough (University of York) - ‘We neither laugh alone nor weep alone, why then should we pray alone?’: Contagious sociability and Dissenting public worship, 1770-1800

Zoom link: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/86481991710?pwd=66XkUN3NJnpRKCbqb82l6YykzR2p0b.1

Presentation of talks:

'Laughing with (and at) our Fellows: The Search for a Sociable Humour in Eighteenth-century Moral Philosophy'

Discussions of laughter in eighteenth-century moral philosophy were haunted by Thomas Hobbes’s infamous declaration that to laugh was to express “sudden glory” at the expense of another person. This made laughter (and all associated forms of humour) appear deeply unsociable. For Hobbes’s philosophical opponents, such as Shaftesbury and Francis Hutcheson, the task was to rehabilitate laughter by demonstrating that it could be a resource for sociability rather than a threat to it. For Shaftesbury, gentle raillery could lubricate social interactions in the coffee house and salon, while for Hutcheson the contagiousness of laughter pointed to its sociable nature. Often missed in scholarly accounts of this project in rehabilitation, however, is that the anti-Hobbesians did not disarm humour altogether because they recognised its use as a critical and pedagogical tool. Once this is appreciated, I argue, then the gap between Hobbes and his critics narrows considerably. To develop the sociability of oneself and others requires a style of humour (Stoic in origin) that will often cause offense to the person it is directed at, even if the ultimate pedagogical purpose is benign.

‘We neither laugh alone nor weep alone, why then should we pray alone?’: Contagious sociability and Dissenting public worship, 1770-1800

In 1792 Anna Laetita Barbauld responded to an attack on public worship by fellow Protestant Dissenter Gilbert Wakefield, asking ‘why… should we pray alone?’ Barbauld celebrated the powerful force of devotional feeling prompted by sociable public worship: ‘So many separate tapers burning so near’, she declared, ‘must catch, and spread into one common flame’. In the combustible political context of Britain in the 1790s, such language risked accusations of political as well as religious enthusiasm, commonly used to attack Dissenting communities. But in this paper I show how Barbauld, alongside contemporaries like Richard Price, Joseph Priestley, and Mary Hays, defended the sociability of public worship. Their treatises staged striking defences of shared devotional feeling using vocabularies of sympathy, contagion, fire, and electric forces, and in so doing, gestured to a grammar of sociability in which the core subject is collective rather than individual.